History: Section 4, Recapture of the Philippines, 1942-45

Japanese Pacific Strategy Commences with the Battle of the Coral Sea

While the Allies had been caught off guard by the early Japanese raids and deferred to their Rainbow 5 Warplan, the Imperial Japanese Army/Navy(IJA/N) had been planning their conquest all the way Southeast through Asia, India, and most strategically of Allied value, Australia. This involved numerous synchronized island hopping assaults through New Guinea(esp. Port Moresby), New Britain, the Aleutians, Samoa, Fiji and other points leading to Australia. Port Moresby, Midway and the Aleutians were greenlighted to Admiral Yamamoto at half requested strength; one carrier group total. This diminished strength was said to have subsequently led to poor IJN performance at the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942, and subsequent pacific island operations. As earlier mentioned, the key military objective of the IJN/A was to establish control of allied passage through the Solomon Islands and ultimately Port Moresby, New Guinea. This would have the effect of isolating and laying siege to Australia. Many tactical errors occurred during the approach to what promised to be one of the largest naval battles in history. As earlier mentioned, the IJN approached Port Moresby at half Admiral Yamamoto’s requested strength due to concurrent Japanese assault operations. Between this issue, coupled with freshly US codebreaker decyphers, the relatively understrength US naval forces were able to disrupt and fully halt the IJA/N attempted landing at Port Moresby.

The US had assigned the USS Yorktown and Lexington carrier groups. Although the Lexington was sunk, the remaining allied forces were able to significantly disrupt the Japanese landing at Port Moresby, whereby the IJN/A abandoned their assault landing there. Moreover, the IJN lost 3 carriers delaying their Midway aspirations. The USN was able to repair the damaged Yorktown, and still had the Enterprise and Hornet carriers, while the IJN had four remaining total. Shown opposite is the famous Jimmy Doolittle bomber squadron, the first allied retribution of the Pearl Harbor attack.

Allied Commanders' Strategy: MacArthur Regroups Command in Australia; Midway, Solomon Islands and Guadalcanal

Now the Allies led by the US military began the reversal of island/atoll conquest initiated by the Japanese in its strategy to isolate Japan by sea and small island air bases throughout southeast Asia. The Allies began to push forward into New Guinea, the remaining Solomon islands, Gilbert, Marshall Islands, the Marianas and Peleliu. Allied submarine warfare had a tremendous effect destroying not only IJN warships, but commercial shipping desperately needed by the Japanese war machine. Meanwhile in China and India, the IJA had designs on major conquests of these territories, rich in natural resources. Indeed, the Japanese had invaded Manchuria and Korea years earlier with devastating brutality. These expeditions proved extremely costly in blood and treasure to all sides, especially China. Many books have been written about the rape of Nanking, a tale of human depravity well beyond civilized comprehension, and are beyond the scope of this essay. Suffice it to say the Japanese military was over extended in manpower, munitions, and in general, logistic replenishment.

Back in Washington, the Joint Chiefs of staff reorganized the Pacific command making MacArthur, now based in Australia, the Supreme Commander for the Southwest Pacific. This included the host of Solomon Chain Islands(including Guadalcanal), the Philippines, Australia, New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the Netherland Indies. Admiral Chester Nimitz was appointed as Head of the Central Pacific Ocean Zone. In early 1942, the susceptibility to Japanese attack and invasion of the entire continent of Australia became a likely scenario, given the Japanese massive imperialist victories throughout central and southeast Asia. Dealt another weak hand, MacArthur had a bare minimum of military resources to defend Australia. The Australian Army and its materiel were not in Australia, but fighting the Nazis in North Africa. The contingents of Army soldiers which began arriving to cover the defense of Australia were very often reserves, National Guard units, unlike the battle hardened Japanese assault troops. The US and her allies had long anticipated war with Japan, just not so soon. Because of the early surprise attacks throughout the Pacific, both men and materiel lagged where they needed to be to mount effective defenses. In fact military resources were so depleted, a line was drawn down the center of Australia from which one side was to be conceded to the Japanese, and Australia would make its last stand from the other side. Looming in the background was the threat of a Japanese Naval blockade, somewhat similar to the siege held for months against Bataan, but for much longer.

Admiral Yamamoto viewed Midway as a key strategic element in establishing air superiority in the Pacific. Moreover, he devised the Midway attack as a trap for the USN as he planned to lure USN ships coming to the defensive aid of the island and subsequently concentrating dispersed IJN naval power to take out the core of the USN’s Pacific fleet.

An unseen but key element of the US military’s strategic prowess was its codebreaking capability, whereby IJN intercepts captured by USN intelligence were learned of in advance of the execution of Japanese military strategy. These codebreakers operated not only on communications between ships and other Pacific island comm facilities, but recent declassification (of tens of thousands of top secret Japanese diplomatic messages sent from the Japanese embassy in Berlin to Tokyo) revealed the advantages the Allies enjoyed in understanding Japanese strategy. The Japanese diplomatic corps, in Nazi Germany, shared their war plans with the Nazis. Hence, the Japanese unknowingly shared many key impending battle plans with the Allies by way of the Nazis. These were ultimately referred to as the “Purple Codes”.

The IJN commenced its attack on June 3rd, 1943, but unsurprisingly all US strike aircraft had abandoned Midway while USN strike aircraft were on their way to meet the attacking aircraft in superior numbers at Midway(a total surprise for the Japanese). Three Japanese aircraft carriers, the Soryu, Kaga, and Akagi, were collectively sunk. The one remaining IJN carrier, the Hiryu, attacked the USS Yorktown, putting her out of action until sunk by the Japanese submarine I-168, along with the the American destroyer USS Hammann. The remaining IJN carrier, the Hiryu, was sunk later that day. Having completely lost the element of surprise and suffering the devastating destruction of the IJN’s Midway task force, the Japanese called off their Midway aspirations on June 5th, 1943.

And so MacArthur and Nimitz mapped out a “tense” strategy(internecine Army vs. Navy glory), one that positioned the two Commanders area of responsibility directly over the Solomon Islands. Nimitz took the first initiative invading Guadalcanal on August 7, 1942 with the 1st Marine Division. Meanwhile, MacArthur was subject to the incremental arrival of largely Reserve troops and disappointingly, very poor weaponry. The first Army units were sent into New Guinea. The Enfield rifle, a bolt action single shot rifle popularized in WWI, was the mainstay small arms provision. Heavy artillery, tanks, flame throwers were still in production in the states. The casualties of these Reserve units was staggering, many experiencing a 90% casualty rate. The next stop for the US Army was New Caledonia…which was held by Vichy French forces aligned with the Axis powers. Meanwhile, the outnumbered Marines on Guadalcanal were becoming bogged down against the Japanese forces and were fighting an enemy force highly dug in with bunkers, tunnels, pillboxes and strategically located elevated points. In October of 1942, Army reinforcements were brought into Guadalcanal to support the American counter-invasion. Enemy bombers, strafers and naval gunfire endlessly pounded Guadalcanal for months, taking a severe morale toll on the men. Now men of the 37th Army division were called upon to attack New Georgia. The fighting there just as intense as Guadalcanal. Fanatical banzai charges led by the Japanese were all uniformly failures.

The US Navy had its own war to fight off the shores of these islands and both sides experienced heavy losses, 6 light and heavy cruisers and 10 destroyers, many sunk, lay at he bottom of the sea as a testament to the ferocity of this warfare. Technically, the Guadalcanal engagement at Savo Island is considered a victory for the IJN, scoring the sinking of 4 USN capital ships before any IJN ships were damaged. Most of the USN Mark 14 torpedoes fired were duds. Moreover, 36 US aircraft and 1700 sailors perished. The US Marines suffered 1200 dead and 2800 casualties, roughly 25% of the Marines total landing force, while the USN experienced the death of nearly 5000 sailors in total. All told, over 30,000 deaths and casualties were dealt upon both the Japanese and American forces. After several months, the Japanese decided to withdraw from Guadalcanal and New Guinea rather than sacrifice their remaining forces. The Battle of Guadalcanal is widely considered the turning point of Japanese invincibility in WWII.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea

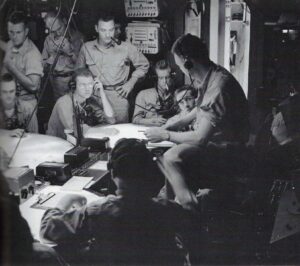

When the US assaulted Saipan, the Japanese high command viewed the repulsion of this action as indispensable in winning the war, and thus required a major operation to fight for. Admiral Ozawa thus assembled a 9 carrier task force augmented by 500 land based attached aircraft. The USN force lead by Admiral Spruance had the advantage of 15 carriers and nearly 1000 aircraft at his disposal. On June 19, 1944, the Japanese attack commenced. However, the USN held a further military advantage, the outfitting of all carriers and capital ships with centralized CIC’s (Combat Information Centers). Generally behind the bridge, these centers fused all the radar, sonar and primitive ECM electronic equipment with commensurate defensive/offensive fire control armaments aboard the ship, including radio contact with aircraft. It is noted that the IJN did not have radar capability(until nearly the end of the war), and generally resorted to reconnaissance aircraft to locate the enemy. The CIC acted as a force multiplier in the battle which was so heavily favorable to the USN, the battle later became known as the great “Mariana Turkey Shoot”. Numerous IJN carriers and assorted classes of all ships were sunk at relatively low losses for the USN. But most significantly, the IJN’s fleet air wing was reduced by 90%, effectively terminating their carrier fleet capability. The Battle of the Philippine Sea was the largest aircraft carrier battle in history.

Battle of Leyte Gulf

The IJN’s loss at the Battle of the Philippine Sea gave them little choice to allow either the Allies to cut them off from SE Asia, or to go on the offensive with their remaining heavy capital ships in a plan devised to trap the USN in the multiplicity of waterway channels in the southern Philippines. This battle took place at Leyte Gulf in the southern islands of the Philippines, Oct. 1944, where General MacArthur walked ashore with his 6th Army troops marking the first steps to take back the Philippines. The map shown on the opposite margin shows an aerial map of the entrapment strategy and the unfolding engagements between the 2 forces. The Japanese still retained formidable strength with many large surface vessels including heavy cruisers, battleships, destroyers and the few carriers who survived the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The Japanese split their task force into 3 sections: northern, southern, and center. Center force was tasked to pass through the San Bernardino Strait into the Philippine Sea and turn southward to disrupt the amphibious landings at Leyte. Southern force was tasked to strike the Leyte landing zone via Surigao Strait while the northern force was to be a deception meant to pull the USN away from Leyte. It is noted that between the IJN’s 4 carriers, they carried a total of 108 aircraft. The USN was effective in neutralizing most, but not all, of center force and then fell for the northern force deception as it began chasing the IJN force northward. Meanwhile, southern force was ambushed by American and Australian Navies and destroyed all but one IJN destroyer. The IJN’s deceptive luring of the USN chased northward, but despite being outnumbered in military ship tonnage and firepower, the IJN made a series of tactical mistakes losing their remaining carriers, 3 battleships, 10 cruisers and 11 destroyers. The USN lost one heavy carrier, 2 light carriers, and 4 destroyers. For the IJN, this was the greatest loss of ships and lives in one battle in all naval history. Furthermore, this spelled the end of what was left of IJN traffic through SE Asia and ultimately Australia.

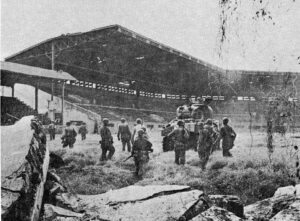

It was on Oct. 20, 1944, that Leyte Gulf became the first beach head assault by the US and her allies to retake the Philippines. The US Army Air Corps(5th Air Force) now enjoyed air superiority which expedited the progress of the 6th Army. In December, the island of Mindoro was seized in preparation for the major troop landings at Lingayen Gulf, (non) coincidentally the same beach head established by the invading Japanese 3 years earlier, on the large main island of Luzon. 175,000 allied troops were rapidly landed and quickly retook the nearby Clark Airbase. Two additional landings occurred at Bataan and, by paratroops, south of Manila, including Corregidor. Although the Japanese high command ordered Manila not to be defended and be left an “open” city(as the US/Filipinos had done at the war’s outbreak), subordinate officers ignored the orders and commanded the Japanese defenders to fight to the last man. This ordeal became infamously known as the Battle of Manila, in which enormously tragic numbers of lives (numbers vary but are estimated at around 100,000) of Filipino civilians were murdered. It is further noted that over 80% of the Japanese defenders did not survive.

The Battle of Manila

In January 1945, the Allied major offensive to capture the key strategic city of the Philippines, Manila, had begun. Elements of the 6th and 8th Army divisions along with glider and paratrooper elements landed at strategic approach points surrounding Manila. They were joined by Filipino guerillas in bringing the fight to the Japanese. However, it was soon found that the IJA’s primary defensive units had withdrawn to Baguio. This was essentially a delaying action meant to consume Allied time engaging these troops while the Japanese prepared for the anticipated homeland invasion. The task of defending Manila and its harbor defenses was left to Admiral Iwabuchi, whom despite his commander’s orders(Yamashita) to destroy bridges and other strategic installations, but to leave Manila city and not destroy it once the Americans arrived. These defenders were ordered to regroup in Baguio where the remainder of the Japanese garrison was grouped. However, Iwabuchi disobeyed the order and he ordered his men to fight to the last man standing, while destroying everything else…. buildings, people, materiel. His personal testament to the bushido code of honor. His last quote “Banzai to the Emperor. We are determined to fight to the last man”. On Feb. 6th, 1945, MacArthur declared that Manila had fallen when in fact the battle had hardly begun. As Allied units encircled and entered the city, the Japanese destroyed everything they left behind. Booby traps were pervasively set up. This warfare differed from all other ground warfare in the Pacific in that it was urban “house to house” fighting, and not jungle warfare. MacArthur’s orders were to attempt to save as much of Manila as possible, but an unfortunate outcome of tactical bombing raids against the Japanese positions along with artillery and tank shells raining into enemy positions, fires inevitably were started and spread. As the Japanese troops began to sense the hopelessness of their situation, they began to turn their anger towards the Filipino civilians. No one was safe, not man, woman or child. Without detailing what has become to be known as the Manila Massacre, every imaginable and unimaginable act of mass brutality was spent upon the defenseless Filipinos. The American commanders had to chose whether to go house to house, paying a huge price for such an approach. Meanwhile the tanks and artillery were already setting the city on fire while not having a meaningful effect on protecting civilians. Ultimately the decision was made to sacrifice the city’s infrastructure, and associated collateral damage, and commence area bombardment which expedited the Philippine’s war’s end at a horrific price. It has been estimated that the city of Manila’s total destruction was attributable to 60% Japanese and 40% American. War is nothing but tragic, but had the American GIs lost too many numbers in house to house clearing, as opposed to shelling and strafing, the war’s end would almost certainly have been extended for an unknown period with much higher casualties. The US was still fighting a war on two fronts. The fighting continued throughout key areas of the Philippines, including the southern islands. By March of 1945, the last pockets of Japanese resistance were crushed. There remain accounts of scattered Japanese soldiers who became guerilla fighters well after Japan surrendered; one man surfaced as late as 1974.

The Hukbalahap fight the Japanese

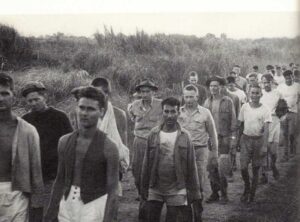

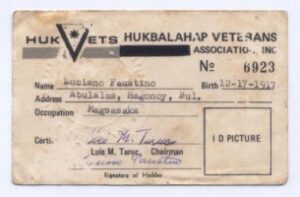

Pre-war, and as far back into Spanish colonial times, a commonly encountered contention existed between landowners and the peasant farmers regarding their meager crop compensation and shelter. Land reform organizations were formed and seesawed back and forth between better and worse treatment, but the issue was never resolved to the point of elevating the farmers out of abject poverty. Once the Japanese invaded the Philippines, a guerilla force comprised of about 10,000 peasants and many more peasant collaborators was formed to fight for their survival. They called themselves the Hukbalahap(or Huks), who emerged in numbers in central Luzon. The Huks were said to hold robust support of both the indigenous peasants, landlords, PCs, and even the USAFFE and often fought side by side. During Japanese occupation, they were viewed as a valuable asset for the Allies and denied enemy control of much of the mountainous jungle and arable land on Luzon. The daring rescue of US POWs from the Cabanatuan Japanese POW encampment encountered the Huks upon freeing and returning the POWs, who ultimately provided rear cover to the Ranger/POW group. Once the Japanese were defeated, life for the Huks did not improve but in fact deteriorated. They were now no longer an asset to the landowners, whom in many cases, collaborated with the Japanese. Pressure of intimidation existed between them and the PCs, the USAFFE, and the landlords, and was widespread in the form of arrest and outright murder of the Huks. A famous case has been recorded of Huk Squadron 77(over 100 men) being massacred by USAFFE Colonel Adonios Maclang’s troops, who were returning from Pampanga. Furthermore, US intelligence viewed the Huks as a threat to political stability and control of Luzon as they had been identified as being aligned with communist ideology. The friction between US and Philippine forces threatened an all out rebellion. Continual mistreatment of tenant farmers and oppression of the Huks, who had even gained 6 seats in the newly formed Philippine Congress(Philippine independence from the US occurred on July 4th, 1946). However, their seats were not allowed to be taken, and further atrocities against the Huks and their allies continued. A violent guerilla warfare was hence conducted until 1954. Reasons for the ending of hostilities were attributed to Huk war fighting weariness, a sentiment of post war indifference among the peasants, and a dampening of PC abuses of the peasants(whom the Huks were constantly fighting for). Although the mainstream historical accounts say that 1954 was the end of Huk hostilities, those of us stationed in Capas witnessed active presence and hostilities through the 1970s.

Final Phase of the war.

Numerous bloody “last stand” conflicts were necessary to defeat the Japanese, including New Guinea, the rest of the Solomons, the Gilbert and Marshall Islands. The two most challenging for the Marines and Army were Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Iwo Jima was a very small atoll sitting in an ideal strategic position for an airstrip for B29s to make round trip un-refueled bombing runs over Japan, and emergency landings. The IJA understood this and spent years digging tunnels and bunkers throughout the rocky terrain. Heavy artillery and machine gun emplacements hidden inland insured the US Marines would pay a heavy price in blood to capture the island. This, despite 3 days of naval bombardment, which did little to destroy their fortified bunkers. The IJA strategy was to allow the Marine landings to commence, but once they began pushing inland, Marines were cut to shreds by elevated and hidden positions in an enfilade of fire power. It was by sheer guts and determination that the 30,000 landed Marines were able to first raise the flag over Mt. Suribachi and a few weeks later had secured the entire island. The cost in lives was staggering: 26,000 US casualties including 7,000 dead. The IJA garrison lost 20,000 men, and surprisingly, captured 1,000 IJA soldiers.

It was known the Japanese Bushido code would make it a near certainty there would be very few prisoners. This code was propagated down to the civilian population, now training women and children how to fight with pitchforks and sharpened sticks. And many were convinced by the IJA high command that the US would do to them what they did throughout the Pacific. Convinced of this, civilians on Okinawa began jumping off cliffs to the their deaths rather than be captured by the evil Americans.

Now, the USN turned its guns on Okinawa for 7 days of heavy bombardment, to be followed by an overwhelming assault force of 183,000 troops(versus 100,00 IJA plus their civilian militia). Kamikaze aircraft filled the skies while the last of the IJN fleet confronted the allied forces. The IJN attempted to lure the USN carrier force towards a group of IJN battleships and destroyers, while 5500 Kamikaze sorties were flown. However, the assaulting task force used submarine screens who spotted these vessels and sunk most of them. After over 2 months of bitter fighting, Okinawa was secured at the cost of 50,000 allied land casualties(including 12,500 dead) and 5,000 sailor deaths. 36 allied ships were sunk, and nearly 400 damaged. 110,000 Japanese soldiers and (42,000 to 100,000 est.) civilians died, many at their own hands.

The allied military and political leadership estimated that allied casualties would be anywhere between 100,000 and 1 million men if the Japanese mainland were to be taken by land invasion. Japanese deaths would perhaps be 10 times higher. Already having captured papers and direct accounts of Japanese tortures and vast murders of POWs, these POWs would certainly have been sacrificed. The same and worse would occur establishing a complete Naval blockade around the island, as famine and disease would certainly come calling. There remained strong resistance, especially by the Japanese elite, to not enter into any surrender agreement with the US and her allies. Indeed, Emperor Hirohito endorsed the war from the beginning. However the US suddenly had a 3rd option, the recently proven atomic bomb. Harry Truman deliberated with his staff and military leadership and decided that its use would certainly be less costly in blood and treasure to the allies, but possibly, yet even probably, result in less Japanese deaths than the first 2 options(indeed, some have argued the first 2 options would have resulted in Japanese genocide between their bushido mentality and the fanatical mass suicides witnessed on Okinawa).

History records the first A-bomb dropped by the B29 “Enola Gay” on Hiroshima, the 2nd dropped not on Kokura 3 days later as its primary target, but on Nagasaki due to weather conditions. The American POW mentioned as “M” in the prior section, who endured the Bataan death march, hell ships, torture and slavery happened to be working in a coal mine in Kokura, would have finally perished if not for the weather that day. Harry Truman patiently waited for a response to the unconditional terms of surrender, for days. Emperor Hirohito, virtually isolated within his palace walls, eventually received news of these bombings, decided to over ride the sentiment of his military leadership and his elites, finally acknowledging that bushido must be released in favor of stopping the loss of life and world suffering. He responded to the terms of unconditional surrender with one condition: that he remain the man-god of the Japanese people. This “demand” was supplanted with alternative wording by Truman stating in essence that the Japanese people could keep the emperor, but essentially as a figurehead and happily the war was over. MacArthur was recruited to become the de facto transition leader of Japan, and almost miraculously, it worked. MacArthur persuaded the war crimes tribunal to absolve Hirohito of all war crimes (although he OK’d and was thus ultimately responsible for all military aggressions starting from Manchuria and other scattered areas rich in natural resources, particularly oil, and throughout WW II). Mac did so as he had the insight of keeping the emperor intact would help foster normalized relations with the temporary US occupation troops. Political independence, subject to non-offensive treaty agreements, occurred during the Korean war. Today, Japan is an important ally in the west Pacific, a bulwark against communist China and Russia.

The cost in non-Japanese civilian lives has been estimated to be over 20 million lives, including 7.5 million lives in China. The combined loss of Japanese lives(military and civilian) has been estimated as high as 3.1 million.

The US Army and US Army Air Force suffered approximately 186,000 casualties including 55,000 deaths. The US Navy suffered approximately 63,000 casualties including 29,000 deaths. The US Marine Corps suffered 67,000 casualties including 19,000 deaths(the Marines are a much smaller force than the USA or USN in percentage of their total numbers, endured disproportionate losses). The combined losses of the Filipinos in civilian and military deaths have been estimated to be as high as 1.4 million.

Comprehensive List of References for Section 4

The Conquering Tide(Ian Toll)

Crisis in the Pacific, The Battle for the Philippines by the men who fought it(Gerald Astor)

National WW II Museum

Ghost Soldiers(Hampton Sides)

NG Atlas of WW II(Kagan, Hyslop, Rendell)

Killing the Rising Sun(O’Reilly, Dugard)

The Pacific On Line War Museum

ww2classroom.org(https://www.ww2classroom.org/)