Japanese Invasion and Occupation: Circa 1941-1942

Pre-war Preparedness

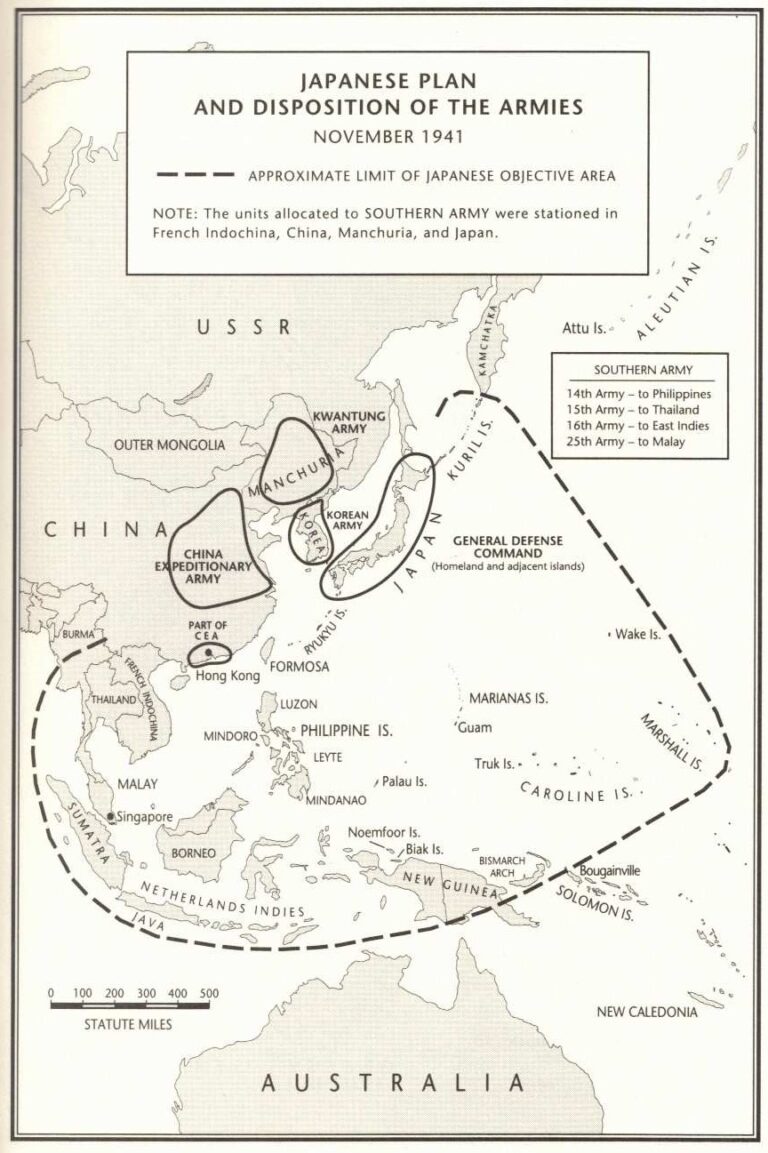

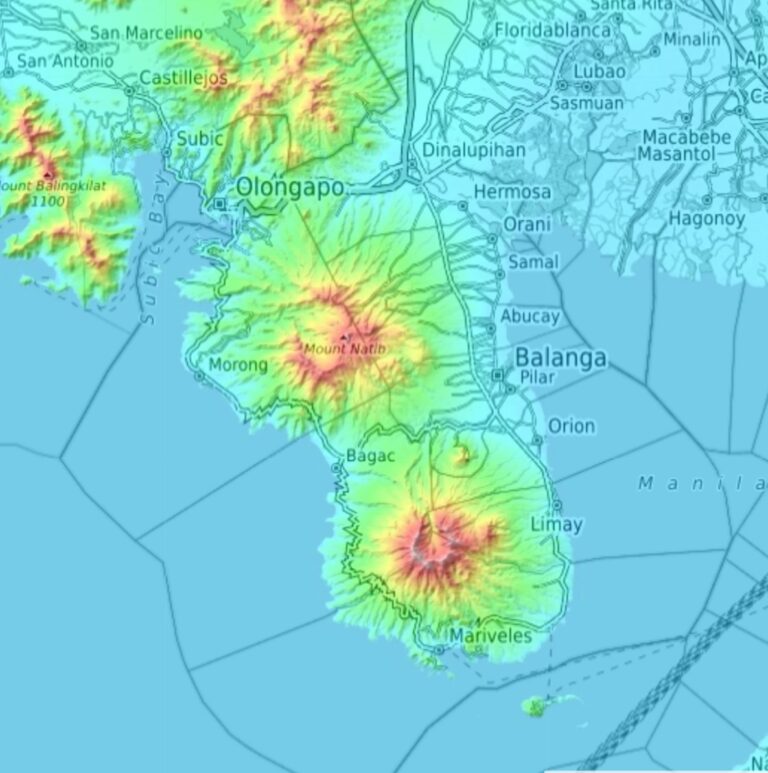

General Douglas MacArthur arrived in the Philippines in 1937. MacArthur’s predecessors had outlined a strategy to defend the Philippines against Japanese invasion(yes, it was early anticipated and thought to be Japan’s primary target) called WPO-1, WPO-2, and ultimately WPO-3. WPO-3 strategized that in the event of an attack, the US and Filipino defenders would retreat down the narrow peninsula of Bataan. This would concentrate those forces alongside of the shore defenses of Corregidor, with its numerous 155mm and 12″ artillery emplacements, and anti-aircraft batteries, while awaiting near term US Naval retaliation and supplies. The plan essentially ran out of time and money to become an effective defensive position awaiting Naval reinforcement. MacArthur hated this defensive strategy presumably due to dependence upon Naval re-establishing success, and instead sought to bolster the islands with large supplies of armaments, ships and troops, so as to make a Japanese invasion too costly to begin with. The Bataan retreat plan was unacceptable to his strategy. He envisioned a force of 40 divisions(400,000 troops), predominantly Filipino, 50 torpedo boats and 250 aircraft scattered across many of the Philippine Islands. However, such a build up would have taken 10 years and $250M(dollars in 1937) and he did not realize time was running out. Additionally, the US was in the midst of its Great Depression and the American sentiment towards war was rather isolationist. Language communications problems arose, such as the Filipino conscripts coming from all the Philippine Islands spoke 8 distinct languages and 87 different dialects. Ultimately, MacArthur’s budget was pared from his initial $25M/year to $1M in 1940.

Thus, seeking to prepare for war with the resources he had, MacArthur took the initiative to centralize the local and American forces into one command structure, the U.S. Armed Forces Far East(USAFFE). It consisted of approximately 12 divisions of US Army, Philippine Army and professional commando Filipino Scouts concentrated on the main island of Luzon. The U.S. embargo of strategic military resources(such as aviation fuel) to Japan had given their military leadership a considerable spark to ignite the war. US preparations for such a scenario was finally approved in the Fall of 1941 to send reinforcement troops, anti-aircraft batteries, artillery as well as air elements. Most of these resources did not arrive before the surprise attack. The materiel that did arrive was often old retired gear from WWI vintage (P-26, P-13, B10,Enfield and Springfield rifles, …), with the exception of 18 B-17s at Clark Field and another 18 in southern Mindanao(Del Monte). The more modernized fighters, P-35s and P40s, were in varied operational readiness. As such, the USAFFE troops were by and large lacking in adequate defensive equipment, in addition to the reality that these troops were not battle hardened. Most strikingly, there was no comprehensive early warning system in place for the Philippines. One primitive radar installation existed at Camp Iba which could resolve azimuth angle and range, but not altitude. Save for a few scouting aircraft, submarines and destroyers newly outfitted with sonar, the Philippines was left highly vulnerable to a surprise attack. The fate of the Philippines appears to have been ultimately sealed by the latest war plan called Rainbow-5, which superceded WPO-3. Rainbow-5 was the Allied command master strategy which assumed the Allies could not fight a war on 2 fronts, and conceded the loss of Guam, Wake, and Philippine Islands, until US Navy and Army troops and materiel were adequate to conduct the counter-offensive, commencing when possible.

On December 8th, 1941(International Dateline is crossed in the mid Pacific, so it was essentially Dec. 7th), fresh rumors that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor stirred the communications channels. General MacArthur’s staff was unable to confirm with any certainty that such an audacious act had occurred, and struggled for hours for confirmation. There were numerous dropped communications throughout the USAFFE command and almost no communications with Naval forces at Cavite, Subic, and smaller installations on the southern islands. However, the radar site at Iba did pick up targets vectoring towards Manila, whose line of sight coincides with Clark field. At this point, the order was given to get the B17s aloft to avoid their destruction, however they ran low on fuel while running racetrack loops, and returned to Clark. It was shortly thereafter that wave after wave of extremely well planned and synchronized Japanese bombers rained down hellish destruction upon virtually all strategic military assets of USAFFE and the US and Philippine Navy with near impunity. John Hay airfield in Baguio, Cavite Naval base, Corregidor, the radar installation at Iba, Subic Bay, Lingayen Gulf, Nichols field, and tragically, Clark field where virtually all the B17s were sitting lined up on the ground. The Del Monte Air field, 500 miles south of Luzon in Mindinao was more a secondary target likely due to its remote location from all the hot targets on Luzon. The fog of war prevailed, it was believed the Japanese had deployed comm jammers as the small contingent of P-40s were unable to coordinate tactics with other pilots on their radios. Japanese saboteurs on the island destroyed land line communications. Before Iba Radar station was hit(still operational), and because it was unable to establish the altitude of the incoming fighters and bombers, the P-40 fighters set up in stacked altitude intervals in an attempt to intercept. The larger problem was the limited altitude ceiling of the P-40s, due to both the old vintage of the aircraft and not having oxygen setups for the pilot. The Japanese approached from as high as 30,000 feet, while the P-40 could temporarily hit 15,000 feet. Coastal defense artillery was supplied with ammunition so old that it was said 5 out of 6 of the shells did not fire. And what little of the P-35s and -40s remaining were poor condition having worn out engines often spraying leaked oil over the pilot’s canope. The Navy’s losses were primarily at the Cavite repair facility where 2 destroyers and 2 submarines were tied in. Light destroyers and PT boats tended to establish a forward seabased defensive line and were almost never tied in at Cavite and Subic. Many larger ships in the vicinity of the Manila Bay area, which obtained accurate reports about the Pearl Harbor attack were immediately ordered to withdraw towards the southern Malaysian territory, as the Australian southern flank (relative to the Philippines) remained of higher strategic value. PT boats from Cavite were able to shoot down several Zeroes. But the lack of substantial AA equipment allowed the Japanese bombers to make practice runs against the Cavite Base from 20,000 feet before finally dropping their ordinance. Cavite Naval Base was essentially destroyed, while one of the submarines undergoing repair was heavily damaged. The destroyers were able to pull out of the Navy yard and engage in AA defense. Finally, the capital city of the Pearl of the Orient, Manila, of no military strategic significance, was ruthlessly bombed. Luzon was now left helpless against a beachfront invasion.

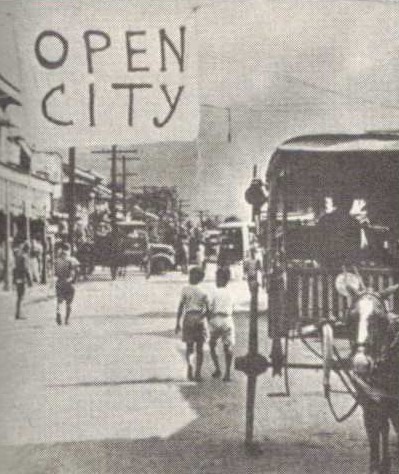

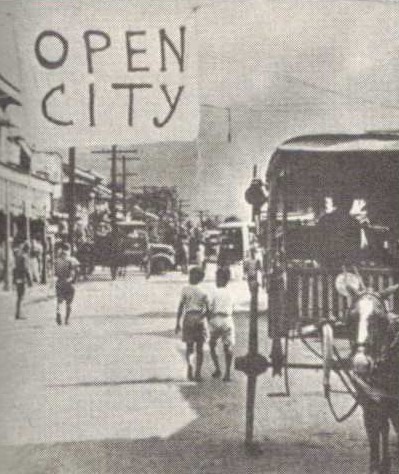

The bombing raid on Luzon was nearly a complete success for the Japanese. Despite Japanese General Homma’s 2:3 troop personnel disadvantage, he had established air supremacy and Naval dominance. There were many understrength but heroic attempts to stave off the fighter bombers waves and impending landings. But too many of the usable P-35s and P-40s would not remain airborne long due to their poor condition. The American and Philippine AF scored a number Zero hits but not enough to be effective in altering the raid. Already, the Japanese established beach heads on the small island of Aparri. The 1 remaining seaworthy submarine from Cavite, along with several subs from adjacent waters were able sink one troop ship, although the remaining torpedoes fired did not detonate upon impact, or missed. It is noted that a contributing factor to the USN’s initial ineffectiveness was due to the dismal performance of the M-14 torpedo, ultimately fixed later in the war. Finally a B17 from Mindinao dropped 3 bombs on a Japanese battleship, with one scoring a direct hit. That Flying Fortress was immediately pursued by Zeroes which crash landed at Clark. MacArthur called President Quezon to recommend establishing Manila as an “open city”, meaning it could not be defended and that it would be saved from annihilation by allowing the Japanese entry. This horrified Quezon but this was the new sudden reality. MacArthur immediately took to his bunker in Corregidor and implemented War Plan Orange. Luzon’s south bound traffic, much of it being General Wainwright’s command of 3 divisions of Filipino troops in northern Luzon, along with several other dispersed divisions traveled on primitive roads, all southbound

Large Scale Japanese Land Invasion Begins

Interservice rivalry has existed throughout military organizations as long as there have been Armies and Navies. General MacArthur and Admiral Hart(the Pacific Asiatic Fleet Commander) unfortunately continued this tradition, having virtually no line of inter-service communication. MacArthur viewed the Navy’s purpose was to maintain incoming defensive posture against Bombers, and to keep troops from attacking as the islands’ defensive network, and that it was an adjunct service to the Army. The Army’s role was strictly land based and meant to defend the Philippines from an on land incursion. So the Navy was not effective in communicating to the Army essential real time intelligence regarding hits, misses, enemy positions and associated strength. The local attack intelligence tended to circuitously flow around lower ranking officers and commands, along with poor quality and disinformation reports. One example was MacArthur announcing to Admiral Hart that Manila was to be immediately declared an open city. Apparently MacArthur did not realize that Manila contained many Naval assets including sub bases, repair facilities and fuel barges. These would all need to be moved lest they fall into the hands of the invaders. However, there was simply not enough time to do so.

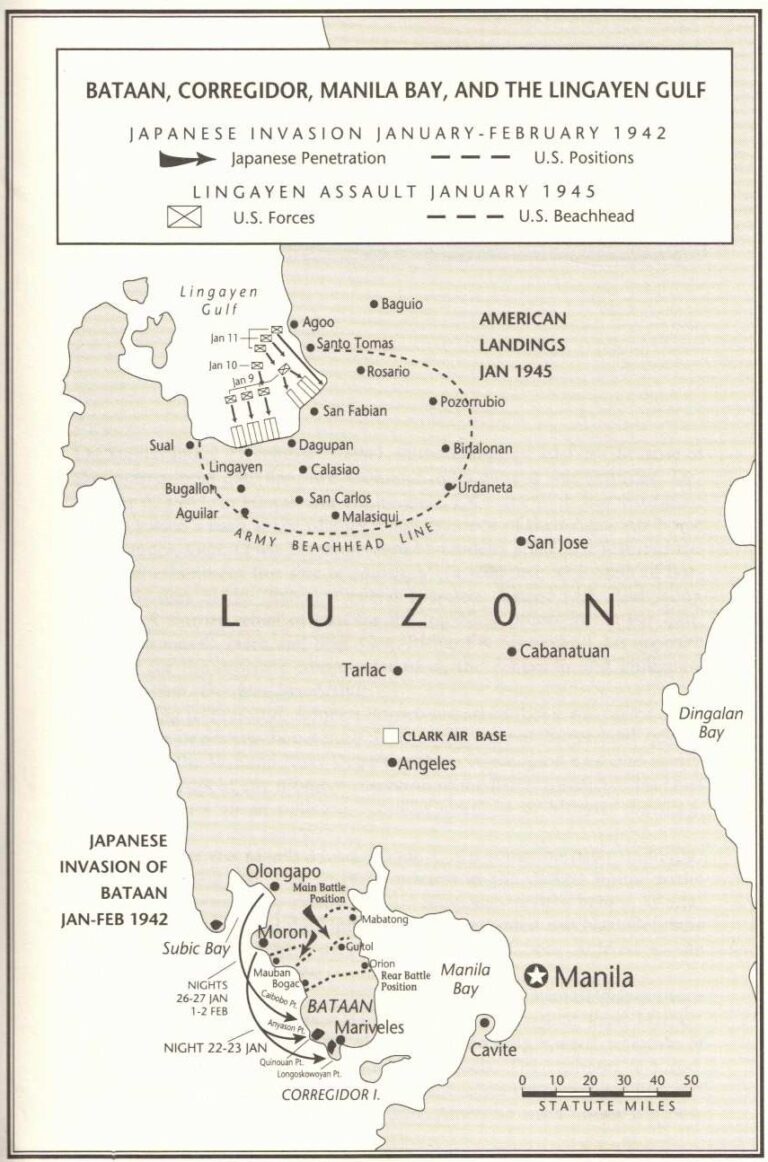

Meanwhile the sudden order of War Plan Orange execution was met with panic and confusion. Approximately 40% of the Philippine USAFFE conscripts/reserves were lost as casualties or desertion, many of the living to return as guerilla warfighters. The remaining troops USAFFE were dispersed across the very large land mass of northern Luzon meant originally to fight off Japanese incursions into those areas. Now they were all simultaneously taking all measures to join the concentrated defenses in Bataan. Many trucks and assorted vehicles were instantly commandeered as troop and materiel transports. What was originally intended to be a defensive force of Bataan, of well organized and trained USAFFE infantry troops became an overwhelming concentration of assorted personnel: many administrators, behind the line troops, Naval personnel, and undertrained, unequipped Filipinos where language communications was poor as best. Nevertheless, these personnel, alongside the professional troops(American and Filipino Scouts), were given the solemn duty of saving the Philippines from the impending attack without the benefit of meaningful air support, and very understrength Naval support. In the end, 80,000 troops and 10,000 civilian refugees crowded down into the small Bataan peninsula.

The initial wave of Japanese troops came ashore on the eastern side of Luzon on Jan. 8th. at Lingayen Gulf. Observation posts on nearby mountains spotted them and USAFFE artillery was sent raining down upon them causing massive Japanese casualties. But the Japanese just sent more men and pushed harder. Many Japanese were taken out by land mine emplacements set up along the beaches(both homemade(like IEDs)) and military grade. Then came the infamous Banzai charge for which the Japanese suffered tremendous losses from machine gun and grenade defenses. The next offensive was augmented with tank, air, and Naval gunfire. A regiment of Philippine Scouts had their rear infiltrated by Japanese snipers, at which time it was decided to install their own hidden snipers in hidden positions which yielded great success. Yet the Japanese troops pushed forward, probing the defensive flanks. On Jan. 10th General Homma offered MacArthur terms of surrender, which were not considered. Japanese appeals to the local Filipinos suggested they would rid the Philippines of Euro-American colonialism, dropping thousands of leaflets over the barrios. Provisions on Bataan were running dangerously low, yet all held out hope, as they had been told by higher level command, that supplies and reinforcements were coming. All troops were put on half daily rations, a tremendous burden when fighting 20 hours/day. There were a few signs of weakening the Japanese assault, one such instance on eastern Bataan. General Wainwright’s orders to outflank this position did produce a temporary stabilizing effect. But the Japanese made gains around other territories of Bataan making the entire order of battle look like a giant jig saw puzzle in constant motion.

The Bataan/Corregidor Defense

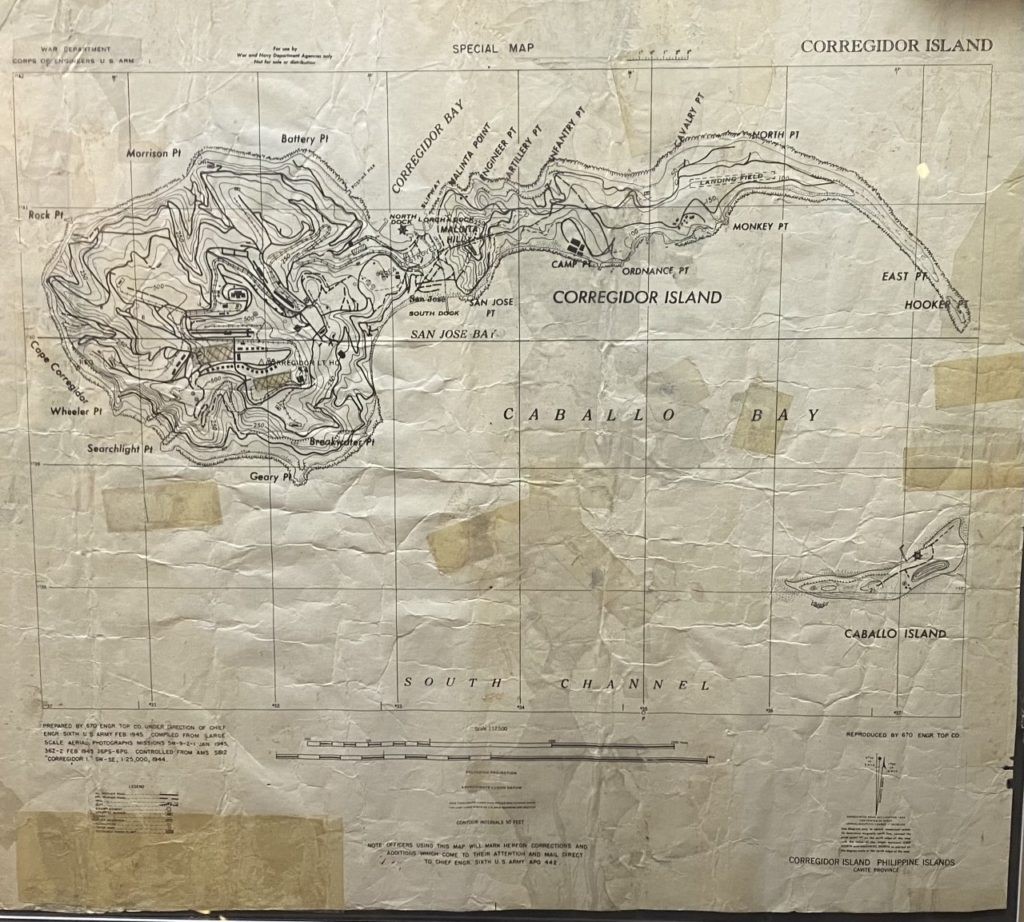

Often called the Gibraltor of the Pacific, or “The Rock”, the 3 square mile island of Corregidor sat as a defensive fortress to Naval Forces attempting to enter Manila Bay. Rugged and of shallow mountains, it was outfitted with harbor defense WW1 era 155mm and 12″ artillery, many antiaircraft emplacements, and an assortment of smaller bore artillery and mortars. USAFFE, US Navy, a regiment of US Marines(from Olongapo), evacuated civilians, along with the bulk of Philippine high command comprised roughly 10,000 personnel on Corregidor. The 600 foot Malinta “mountain” had long ago been bored out to establish a hardened bunker for staff, communications, supplies, munitions, and a field hospital. It even had a light gauge railway to move the supplies about. US and Filipino civilian personnel attached to the military were evacuated to Corregidor once the Manila open city policy was initiated. The Japanese heavy bombers released from high altitudes where AA flak and fighter interception was ineffective. Zero dive bombers tended to avoid the strategic, well defended and accurate AA batteries on Corregidor. Again, without high altitude defenses, the Japanese bombers would take 2 or 3 practice runs over “The Rock” to optimize their approach and finally let loose with their ordnance. Meanwhile, MacArthur exhorted his forces to fight on in their defensive posture because reinforcements, armaments and supplies were on their way. Whether he knew they weren’t per Rainbow-5 strategy, or truly believing the Philippines would be not be conceded to the Japanese by the American military, we will not know. These shipments were indeed on their way across the Pacific, but destined for Australia and not the Philippines.

The Battling Bastards of Bataan

The Japanese air power and artillery continued to pummel Corregidor and especally Bataan, while US air power was reduced to a several residual aircraft used for reconaissance and occasionally called in for straffing runs. Now all means of land line communication were cut, so only encrypted HF radio msg’s remained to communicate across military ground forces. Communications with military command in the states was sporadic and confused. There existed a seesawing of both offensive and defensive positions, both sides made progress often to lose gained ground from counterattacks and many mistakes. The Japanese filled the jungle trees with snipers so that whenever USAFFE advanced to new ground to set up artillery positions, they either paid dearly for it in blood, or else retreated. The success of the 57th Regiment of Philippine Scouts were initially successful in stopping the Japanese cold on the east end of line defensive line, but jeopardized by the collapse of the defenses on their left flank. The 45th and 31st Regiments requested a tank assault against the northern defensive line which had stubbornly cast off all attempted assaults on it, but the tank commander refused, insisting the rugged terrain was not suitable for tanks(in review, it was well suitable for tanks, largely flat). Too many of the Philippine USAFFE troops had no small arms. The US command pulled back and made a priority of defending their left flank by running suppies and materiel up an obscure road shown on their maps. It turned out this was a narrow trail, unsuitable for any vehicular traffic, so they had to ferry the suppies on slow moving pack mules(WPO-3 plan never verified the utility of this or any “road”). Logistical ignorance exacted a high toll. Despite harassment from Japanese Zeroes, most of the supplies reached their destination. General Fitch relayed a message to General Wainwright not to fire upon any barges coming down the coast, as they were said to be provisions(those barges never arrived). Instead, it gave the opportunity of small enemy landing craft the chance to disembark. Many of these were intercepted by Navy PT boats and sunk, which created chaos among the Japanese whose remains ultimately landed at Longoskawayan Point and Caibobo, many miles from their objective. The most endangered position now stood at Mariveles at this point, and an Naval squadron of PT boats, accompanied by Marines(who were also tasked with training Filipino Reserves in warfighting) were ordered to defend it. An unfortunate fact was that the newly formed infantry regiments defending Bataan were cobbled together with non-infantry trained personnel along with well trained troops. As such, one can understand the erratic nature of the defensive gains and losses. A dead Japanese soldier’s diary described in his diary the spotting of an American “suicide squad”. This siting turned to be Navy sailors dressed in their whites who were set up at night chatting and smoking cigarettes, for which the Japanese assumed they were being used as decoys to attract an ambush.

In late January, a company comprised of Philippine Constabulary forces(PCs) were called in to eliminate a Japanese position endangering the main road supply route to Bataan at Mt. Pucet. The frontal attack was successful, but the PCs were reluctant to work off their flanks, insisting to stay on the road. The commander(Alexander), requested heavy guns mounted on carriers to displace the Japanese on Mt. Pucet. The carriers happened to be very noisy, allowing the enemy to prepare to knock it out, which they did indeed. The numbers of dead and wounded were devastating. Artillery support from Corregidor was minimally effective, since its flat trajectory shells could not be lobbed over the protective mountain ridge at Bataan. Days later, a USAFFE counterattack was launched, without success. But the USAFFE forces persisted, Philippine Scouts attacked enemy emplacements at Longoskawayan, at times resorted to hand to hand combat, and ultimately swept the Japanese out of their positions there. Quinauan Point remained in a heated battle with the Scouts for which more Scout reinforcements were called in. The Japanese were experts in concealment and camouflage, digging large bell shaped entrenchments which allowed only one soldier and his rifle to pop up through the surface hole, while other troops hidden below could replace the rifleman if out of ammo, or shot. It took a bit of practice for the Scouts to learn their enemy’s tactic, and their expert sharpshooting became highly effective in picking off the enemy “gophers”. Captured enemy warplan documents revealed that the Japanese now planned a seaborne invasion at Mariveles. This grand stroke of luck allowed USAFFE to ready artillery and amass troops there, while the few remaining intact P-40s were called upon to strafe the enemy landing barges. While all the landing barges were sunk and over half the enemy attacking force dead, nevertheless, around 400 enemy troops managed to land at Mariveles. The remaining US Navy PT boat squadron blasted away at these troops, while shore based artillery and riflemen took out a large portion of the remaining enemy. The war was becoming increasingly ruthless. Virtually no prisoners on either side were being taken, revenge running hot through the veins of both sides. Japanese reinforcements were requested for the Mariveles raid were denied, but enemy command decided to rescue the seaborne stragglers. Again, their tactical plans were intercepted and the Japanese rescue team was annihilated. Still, the Japanese ground offensive persisted with tight coordination, while USAFFE troops struggled to maintain seamless defensive lines. Various USAFFE factions fought with eachother for possession of the heavy artillery and machine guns. The Japanese began setting up “pockets” behind USAFFE defensive lines, which were found to be extremely difficult to neutralize. General Wainwright was now in command of all defensive forces with the objective of eliminating the Japanese emplacements at the pockets and points(potential landing points). When asked by a Navy officer what he had to offer his men, Wainwright responded with “morale”, as there was little remaining ammo, food, reserve troops, aircraft, or boats. Against all odds, Wainwright’s troops brought forward their remaining tanks and guns, and at a heavy cost, swept out all enemy troops in the pockets and points.

Both sides of the war suffered heavily from disease and exhaustion. Malaria, dysentery, starvation and exhaustion prevailed on both sides. A lull fell over Bataan in February, a case of good news and bad news. The reason was that the Japanese were gathering reinforcements, supplies and equipment; while the USAFFE troops only gathered a couple of weeks of rest. They would receive none of what the Japanese were receiving. Army cavalry units now slaughtered and ate their horses, stray caribou were immediately slaughtered for their meat. At one point, nearly 7,000 troops lay in Bataan’s and Corregidor’s field hospitals. Japanese dropped pamphlets throughout the Philippines urging them to surrender so that they would be rewarded with big meals and humane treatment. The Filipinos didn’t buy it. Now troops were on 1/4 daily food rations. It was on this account that the Japanese controlled the supreme advantage, time. The enemy war planners knew they could take their time readying for a renewed assault with plenty of troops, food, and materiel. MacArthur had told his staff he would die before surrendering the Philippines. However, higher powers to be(General Marshall, President Roosevelt) believed MacArthur to be an indispensable war strategist and ordered MacArthur to be secretly evacuated to Melbourne, Australia. On the evening of March 11, 1942, General MacArthur boarded PT boats with his wife, child and numerous staffers. Despite the risks involved by the Japanese Naval blockade, the Navy skipper found a narrow escape route, and headed for Del Monte, Mindinao. After an intermediate refueling stop, they reached their destination from which the MacArthur entourage boarded a B-17 for Australia. It is noted that MacArthur thus became the Pacific theater supreme commander of all allied forces…except the Philippines, for which General Wainwright was awarded this grim duty. It was enroute that General MacArthur spoke the words to his staff “I shall return” which was widely circulated in the global press and of course the exhausted and nearly starving troops on Bataan. But the real question was, When? It should be realized that since December of 1941, the Japanese had established a de facto siege on the USAFFE forces. No reinforcement troop ships, no cargo ships with ammunition or food, no air drops could survive the encirclement of Bataan by the Japanese Navy, Air force, AA batteries and land forces…save for the small quantities of materiel that could sneak through the the Japanese Naval encirclement by submarine. Both American and Filipino troops had greatly respected Mac’s command, and it seemed the Filipinos understood better the reason for his evacuation. This was not the case with American NCO troops who grew hotly resentful, and created the following well known chant:

No Mama, no papa, no Uncle Sam

No aunts, no uncles, no nephews, no nieces

No rifles, no planes, or artillery pieces

And nobody gives a damn

We’re the Battling Bastards of Bataan

Final Defensive Unconditional Surrender

It strains the imagination that MacArthur was shortly thereafter awarded the Medal of Honor “for conspicuous leadership in preparing the Philippine Islands to resist conquest, for gallantry and intrepidity beyond the call of duty”, in what was ultimately become the largest surrender of American forces in history. Meanwhile, supplies to the Bataan troops continued to dwindle especially when considering the “siphoning” process which became standard. Aside from the small quantities of new supplies which occasionally arrived by cramped submarines able to penetrate Japanese Naval patrols, the dwindling supplies to Bataan principally arrived from the Corregidor mountain bunker. As these were passed from one transit point to another, each organization pulled excess supplies for their own. Serious dietary deficiencies spread amongst the weakened men including scurvy, beriberi, malaria, dengue fever and amoebic dysentery. Now General Wainwright assessed his situation of the remaining 80,000 troops cornered into a 200 square mile portion of the Bataan peninsula. Army doctors assessed that less than 45% of these troops were rated as combat efficient. 25,000 fresh Japanese troops poured into the region surrounding the USAFFE troops. New air elements arrived as well. Heavy artillery rained down upon the troops ceaselessly. Japanese sappers crawled through perimeter wires and inflicted death and chaos among the USAFFE troops. The main defensive line had been broken. Mariveles was ordered to be abandoned, and to destroy all remaining armaments there. The final stand was to be made on the west side of Bataan. Defeat was palpable, men from all USAFFE organizations began swimming across the channel to Corregidor. Back in Australia, MacArthur got wind of the possible surrender of the USAFFE forces. He had fancied numerous breakout plans, and desired to extract the highest cost from the enemy. He even contemplated breaking through to the Zimbales mountains to conduct guerilla warfare against the Japanese. Perhaps if the troops were fresh and combat ready, there might have been a slim chance of this working. But the remaining weakened troops were being pushed back towards the sea. General King of I Corps on Bataan had now to consider surrender or having all his men killed off piecemeal, and he chose the former on April 8th, 1942. Bataan was finished. Only General Wainwright’s troops and personnel remained on Corregidor, continuing to shell enemy positions, while he and his troops were endlessly hammered with relentless artillery and strafing runs. The enemy, having captured the dominant USAFFE forces, then turned their attention to Corregidor. The cost in blood was growing increasingly untenable, roughly 800 defenders along the beach head had already died. The defenders had been initially able to resist the onslaught of bombs, artillery and the amphibious arrival of fresh Japanese troops, but now cornered, outgunned and outnumbered, the troops on Corregidor were ordered to destroy all weapons and ammo. And so it was on May 6th, 1942, General Wainwright radioed President Roosevelt “With broken heart and sadness but not in shame I report….that today I must arrange for the surrender of the fortified islands of Manila Bay.”

Comprehensive List of all text References:

Crisis in the Pacific, The Battles for the Philippine Islands by the men who Fought them; Gerald Astor

The Conquering Tide, Ian Toll

National WWII Museum

US Army Airborne and Special Ops Museum