History Section 3: Bataan Death March and O'Donnell Internment at Capas, Tarlac

Staggered Surrender and POW Disposition

It is rare that the confluence of the numerous negative factors following Wainwright’s final surrender would work in so many ways to imperil the USAFFE POWs. One may consider an array of these factors as simultaneously aligning.

-The Japanese troops who had survived through to the USAFFE surrender, had a score to settle with the Philippine defenders. The Imperial Japanese Army high command had anticipated a relatively short campaign, along with light casualties. This was of course not the case as the defenders were much larger in numbers than their intelligence had assessed (they believed the Islands(concentrated in Luzon) were held by 40,000 troops, not 120,000 including reserve units). General Homma was disciplined by Japanese high command for taking 4 months, not 3 weeks as originally anticipated, to conquer the Bataan and Corregidor defenses, and was subsequently reassigned to bureaucratic military duty in Japan. Revenge was hot among the veteran Japanese troops who suffered heavy losses.

-The siege of Bataan substantially weakened the defending survivors due to disease and malnutrition, such that they were physically exhausted and emaciated, many barely able to walk.

-The Japanese never formally signed the Geneva convention, governing the humane treatment of POWs.

-The sheer number of POWs surrendered surprised and overwhelmed the Japanese command. There was barely a logistical plan for the smaller anticipated number of POWs. The Japanese high command did not want large numbers of combat troops absorbed into POW guard duty while their imperialist offensive ambitions demanded their presence.

-The Japanese Army(IJA) training was particularly brutal, some would say sadistic. Daily hazings and beatings were administered to the recruits for the most minor infractions. The Japanese Army culture was unforgiving towards its own troops, one can imagine how they might handle POWs.

-Perhaps the worst aspect of the POW catastrophe was cultural. Not only did Japanese domestic propaganda assure the Nippon Empire that they were a superior race of people, but the soldier’s moral code of bushido was written into the conscience of all. Meaning that it is dishonorable to surrender and it is the combatant’s duty to fight on to the bitter end of one’s life regardless of any circumstance. The POWs, American and Filipino, were uniformly perceived by the Japanese as sub-human life forms who deserved little or no decency from their captors for not fighting to the death. Of course, huge numbers of USAFFE forces did fight till their deaths.

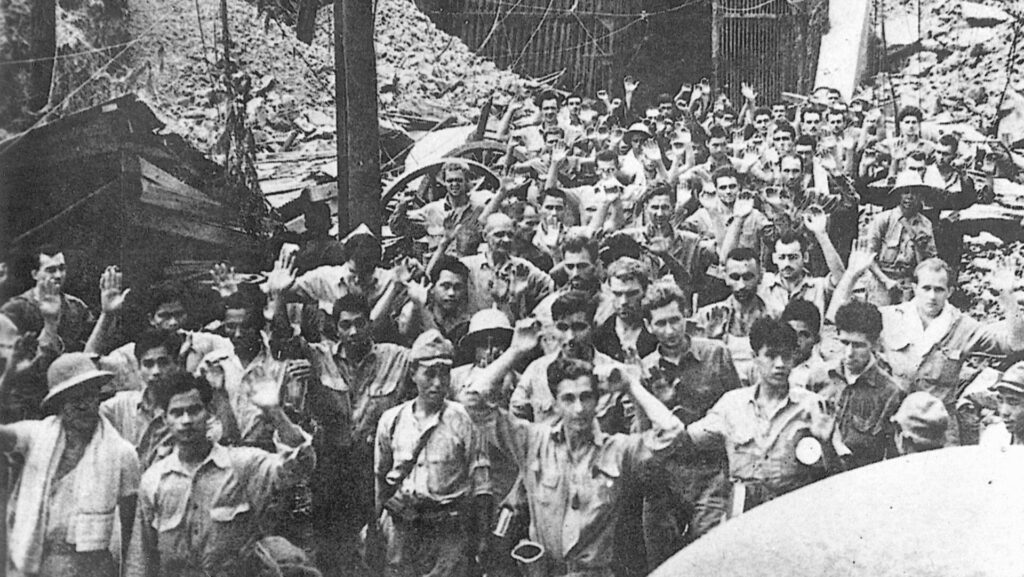

The surrender came in stages, on Bataan, General King surrendered in the face of what was looking to be a genocidal defense of his I Corps which from all perspectives appeared unwinnable. The new momentum of fresh Japanese troops in winning battles in rapid succession, as well as the USAFFE notion of never surrendering, now suddenly perceived as an alternative, pulled most of the Bataan USAFFE commanders into the new reality and followed suit. The last holdout was Wainwright’s force on Corregidor. After the fall of Bataan, weeks passed until Wainwright coordinated the unconditional terms of surrender to General Homma’s satisfaction. This included the surrender of all USAFFE troops in the Philippines including the large numbers in southern Mindanao. Although General Sharp’s Mindanao troops were in a better fighting defensive position than those on Luzon, the implications of the dialogue between Wainwright and Homma implied blackmail…that Wainwright’s non-cooperation to surrender Mindanao would result in an overwhelming offensive and slaughter of the entire defensive garrison at Corregidor. And so it was, Wainwright ultimately signed the terms of unconditional surrender of the entire Philippine defensive forces to the Japanese on May 6th, 1942.

The first group of captives(the largest) were the Bataan defenders. Their sheer numbers(and deteriorated physical condition), coupled with their captors perspective of the POWs being inferior people, set the stage for what would be historically recognized as the Bataan Death March and Capas internment. Those captured on Corregidor and other southern islands, including Mindanao, were taken to Philippine prison facilities(Bilibid, Cabanatuan) or taken by “hellships” back to Japan to be used as slaves, most supporting the mining needs of the Japanese war machine.

The Bataan Death March

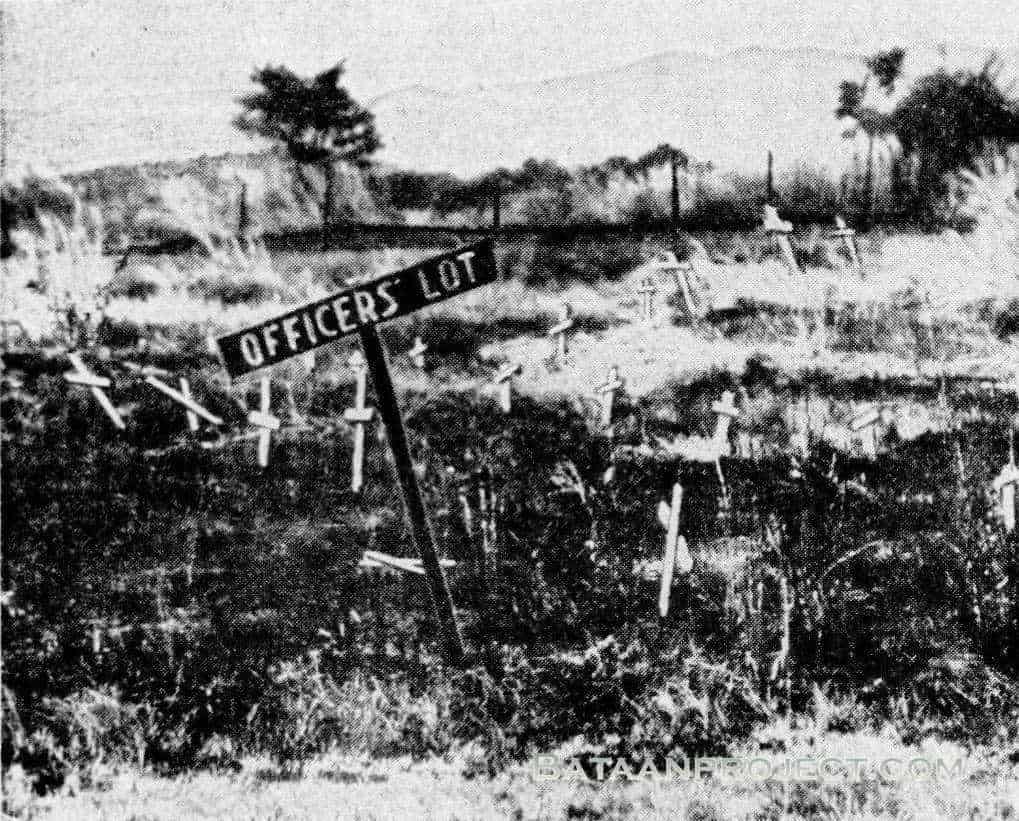

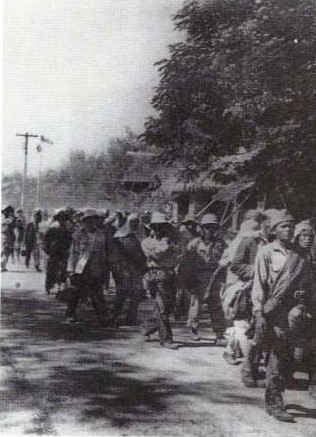

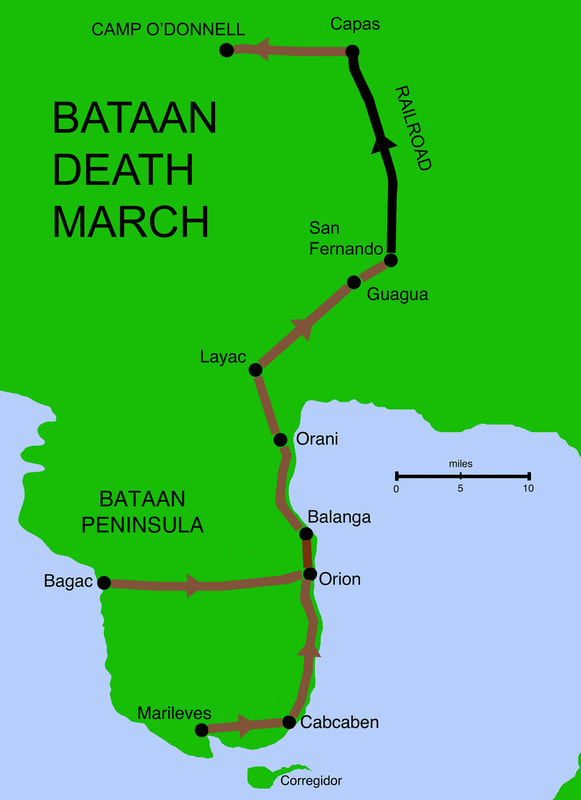

And so the American and Filipino POWs captured on Bataan were dealt the unfortunate card, in large part due to their sheer numbers(in excess of 50,000 men, the Japanese anticipated approximately 25,000), to embark on a forced march of 66 miles from the Bataan peninsula to San Fernando with a final railcar destination of an old Army training base named Camp O’Donnell in the town of Capas, of the Tarlac province. No distinction was made of officers and enlisted men, save for their burials. One Colonel Vance, was roundly beaten while under interrogation, made to sleep on the ground and for days was deprived meaningful sustenance for life. The POWs were first stripped of all personal possessions. Any resistance to this process was met swiftly with a rifle butt to the head, if they were lucky. Rings that met resistance of being given up were said to be removed with the prisoner’s entire finger. 8,700 Americans were then segregated from the 42,000 Filipinos. All POWs on Bataan suffered from varied types of aforementioned diseases and near total exhaustion, not exactly fit to embark upon a 66 mile forced march.

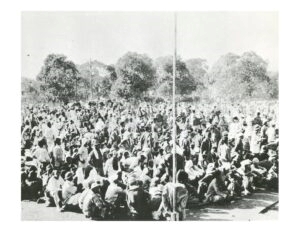

The physical abuse of the POWs was compounded by the absence of logistical planning. Food, water, medicine(particularly quinine to treat malaria) were dealt with largely by what was available along the march, or what short residual, hidden supplies sold between them as contraband. Water supplies were uniformly tainted, found alongside roadside ditches and polluted streams. Food, when available, was largely limited to a sort of rice porridge contaminated with insects and maggots. Those desperate enough to break ranks and make for a roadside water source were greeted by a rifle butt to the head, or a bayonet to wherever was the guard’s choosing. As Japanese trucks would pass the columns, the troops made a sport of hitting the sidemost man in the column with rifle butts or large bamboo canes. As the POWs passed through the Filipino civilian barrios, many acts of mercy were made to both American and Filipino prisoners. They would offer handfuls of rice, sugar wafers, water…but if a guard spotted this, both the giver and receiver were mercilessly beaten. The general rule was that those who fell behind, fell down and were unable to get up, or broke from the ranks were, if lucky, mercilessly beaten. But usually shot or bayoneted. There were instances of particularly sadistic soldiers who felt they needed bayonet practice and would arbitrarily grab a POW from the line, remove him from sight, and conducted live bayonet practice. It may have been considered merciful that the Japanese conducted a small portion of the forced march at night where faster progress to San Fernando would have been possible, but it was simply expedient of their mission to do so. Almost as if to wither the huge numbers of POWs, they continued not only to keep up the daytime march during the Philippine hot, dry season but conducted “sun treatment” rest stops(see above image). The direct sun upon unshaded Philippine terraces accelerated dehydration and what was left of the prisoners’ immune system. Any attempts to crawl into the shade were met with the bayonet. Instances of suicide began, POWs jumped off of bridges, and subsequently shot. The intermediate destination of Lubao had one running water spigot, for 4000 men.

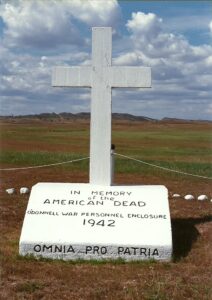

The tormented march lasted 2 weeks and was terminated at the railway head at San Fernando. Finally the POWs could count on some type of break from their marching misery. By this time, those who had shoes had their sides split out and the condition of the men’s feet was uniformly an unbearable soreness, covered with blisters or exposed flesh either infected, or about to be. Here they were loaded onto freight cars normally used to haul livestock, typically 15 horses per car. Into these cars were loaded 100 men each, packed so tight it was impossible to sit. Once the doors were closed, the unventilated stifling heat took yet its further toll. Many men died standing on their way to their semi-final destination, Camp O’Donnell.

O'Donnell POW Internment at Capas, Tarlac

Comprehensive List of all text References:

Crisis in the Pacific, The Battles for the Philippine Islands by the men who Fought them; Gerald Astor

The Conquering Tide, Ian Toll

Andersonville of the Pacific, The National Endowment for the Humanities(neh.gov/article/andersonville-pacific)

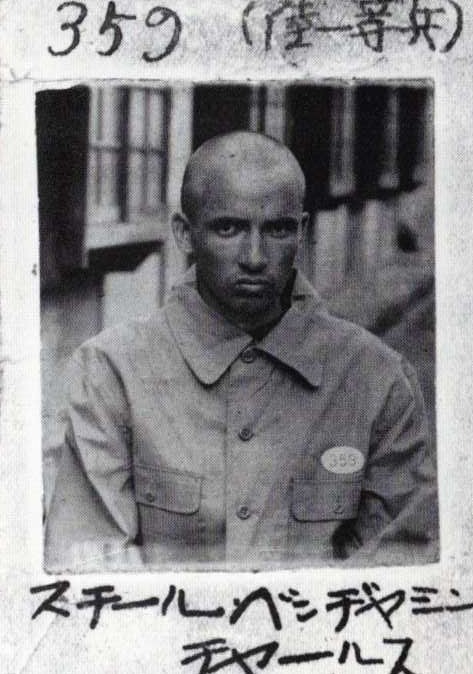

Tears in the Darkness, Michael and Elizabeth Norman, Ben Steele

American Ex-Prisoners of War, Department of Veterans Affairs

National WWII Museum

US Army Airborne and Special Ops Museum

Medium Website; “Bataan Death March is Nothing but Propaganda” (https://medium.com/@JapanDetail/bataan-death-march-is-nothing-but-propaganda-a83fea018a7c)